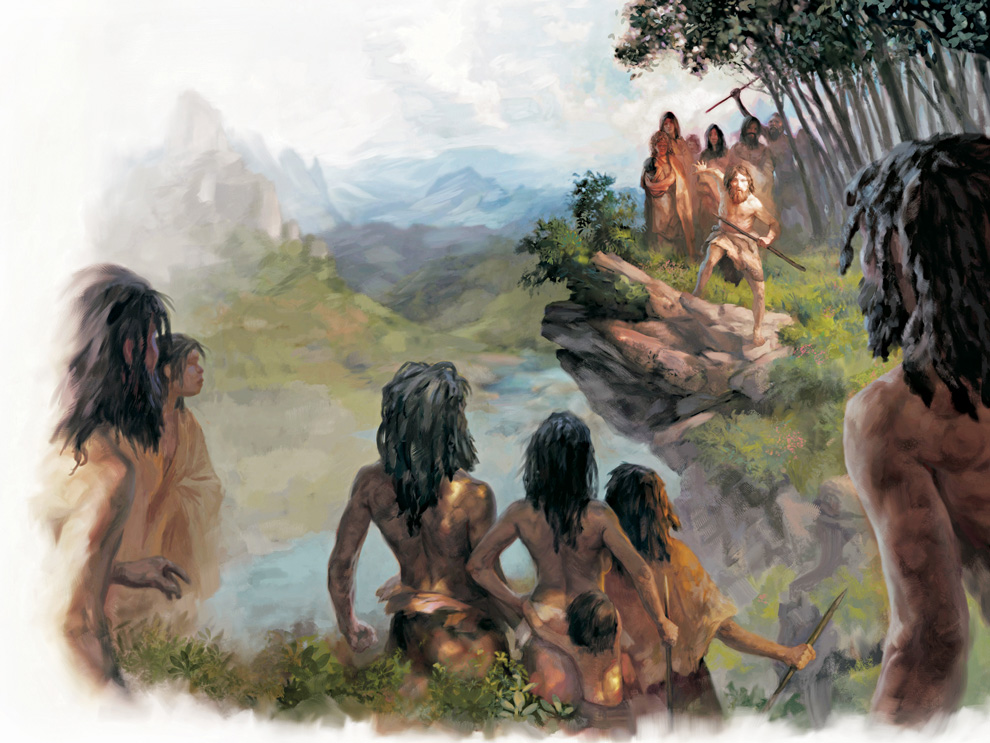

First meeting between modern humans and Denisovans circa 45,000 years ago, arguably somewhere in central or eastern Eurasia. Picture copyright National Geographic Magazine 2013.

First

meeting between modern humans and Denisovans circa 45,000 years ago, arguably

somewhere in central or eastern Eurasia. Picture copyright National

Geographic Magazine 2013.

Last

of the Denisovans

The

Preface to Andrew Collins' new book The Cygnus Key, complete with a comprehensive

preview of its extraordinary findings regarding the origins of civilization

This is the preface to my new book The Cygnus Key: The Denisovan Legacy, Göbekli Tepe, and the Birth of Egypt. It was inspired by an image that appeared (and used here alongside this webpage) in a National Geographic Magazine feature on the extinct hominin species known as Denisovans titled “The Case of the Missing Ancestor,” written by Jamie Shreeve and published in 2013. It shows the hypothetical first meeting between our own modern human ancestors (Homo sapiens) and surviving Denisovans, somewhere in either central or eastern Eurasia. I pondered over this image long and hard, and finally came up with the following scenario, which although fictional, might be how it went down some 45,000 years ago ...

The

date is approximately 45,000 years ago; the location, a mountain pass somewhere

in the Altai-Sayan region of southern Siberia. From a rocky vantage point, four

tall, darkened forms emerge into view from behind a patch of cold early-morning

mist. They stand a few meters apart, gazing toward the only path permitting access

to the mountain’s central plateau.

Each

figure is of extraordinary size, being as much as 7 feet (2.15 meters) in height.

Their stature is that of giant wrestlers, their enormous frames accentuated by

broad shoulders and streams of furs that immerse their bodies from head to feet.

Their heads also are of incredible size, being both long and broad, with large,

powerful jaws. What little can be seen of their exposed skin suggests it is brown;

their long, matted hair dark also. Adding to the almost alien appearance of these

strange individuals are their extremely large noses and unusual eyes, which have

striking black pupils and irises so pale they seem almost white. Completing the

picture are the long, dark feathers attached to their furs, which blow about in

the gentle breeze that has followed the first light of day.

They

are Denisovans, members of an archaic human population whose very existence had

gone unrecognized until the first decade of the twenty-first century, when oversized

fossil remains were discovered in a large cave in the Altai Mountains of southern

Siberia.

The

purpose of these four figures at the head of this rocky pass is to await the arrival

of others—a new people from a distant land located in the direction of the

setting sun. In small groups these people have been approaching ever nearer to

the Denisovans’ mountain retreats, and now, finally, they were within sight,

moving slowly toward the Denisovans’s elevated position. These intruders

were shorter and more slightly built, their heads smaller and more elongated.

Furthermore, their approach to life seemed quite different. They enter new territories,

assume control of them, and exploit their natural resources before dispatching

some of their growing number in pursuit of even more suitable places of occupation.

They have been advancing in this manner for many thousand years, encountering

and even interbreeding with the Old People of the West, who will one day become

known as Neanderthals. For countless millennia the Old People have occupied vast

swaths of the western Eurasian continent, while the Denisovans have been content

to remain in the eastern part of the continent.

Now,

finally, the New People had arrived in the Altai-Sayan region, and were about

to encounter a small group of Denisovans for the very first time. Their advance

party was perhaps ten to twelve in number. They too wore furs to combat the colder

climate found at these higher altitudes, and in the hands of some of them were

long wooden spears. One, the leader of the group, was brandishing his weapon in

a provocative manner, as if ready to attack at the first sign of aggression from

the tall strangers.

Yet

the Denisovans say and do nothing. They simply stand their ground, gazing down

at the intruders, who are now shuffling to a halt no more than 15 meters away.

The

leader of the New People seems unsure what to do. Should they advance further

and strike out at these people who look like tree trunks? Why did they not attack?

More pressingly, why did they not carry weapons? What strange magic was this?

Were they powerful shamans who did not need weapons? Could they kill simply by

making eye contact? Could they send out spirits to torment the families of intruders?

The

Denisovans were indeed powerful shamans. They knew that any confusion or uncertainty

in the minds of the New People would cause them to question their actions. What

is more, the plan was working. They approached no further. A few final thrusts

into the air of the leader’s spear did nothing to prompt a response from

the Denisovans, who simply stood their ground, unfazed by what was unfolding in

front of them.

Unnerved

and fearful of their enemy’s powerful magic, the New People all at once turn

around and retreat back down the mountain pass and out of sight. The Denisovans

have won the day. Yet they know full well that eventually the New People will

return, this time in much greater numbers. Eventually the intruders will overrun

the Denisovans’ world, spelling an end to their population. It might take

a few decades, a few centuries, or even a few millennia, but it will happen.

In

the future the preservation of the Denisovans’ profound ancient wisdom, accumulated

across hundreds of generations, will become the property of the New People. It

will be through them that the Denisovans will continue to exist. Yet this will

not happen through conquest or submission, but through interbreeding. The last

of the Denisovans will give way to hybrid descendants, who with an entirely revitalized

mind-set will continue to thrive, not just in the Old World, but also in the far-off

American continent. Sadly, however, the Denisovans were aware also that for many

millennia knowledge of their very existence will be suppressed, belittled, and

finally forgotten. Yet one day, as the prophecies determine, they will rise again,

their contribution to the genesis of civilization laid bare for all to see. Then,

finally, everyone will know the legacy of the Denisovans.

This

is an imagined first meeting between anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens)

and the last of the Denisovans (tentatively Homo sapiens altaiensis). It is based

on what meager evidence we have regarding their physiology, behavior, genetics,

and technological achievements, along with local folklore, which perhaps preserves

a memory of their former existence in the region.

Whatever

the accuracy behind this all-important encounter between our own ancestors and

the Denisovans, the chances are it occurred around 45,000 years ago either in

the Altai Mountains, where their fossil remains have been found in the Denisova

Cave, the type site of the Denisovans, or a little further north in the western

Sayan Mountains. (A type site is a site that is considered to be the model of

a particular archaeological culture.) These straddle the republics of Khakassia

and Tuva, between which is a narrow strip of land constituting the most southerly

part of the Russian province of Krasnoyarsk Krai. Here age-old folk stories speak

of the former presence of a giant population that inhabited the nearby Yenisei

and Abakan river basins. They recall how these giants created the first stone

fortresses (kurgans), the first irrigation channels, the first dams and bridges,

and even the first divine melodies played on musical instruments.

The

description of these legendary giants best fits what we know about the Denisovans

who occupied southern Siberia for hundreds of thousands of years before their

disappearance around 40,000 years ago. DNA analysis of many modern populations

in East Asia, South Asia, Indonesia, Australia, and even Melanesia and Micronesia,

tells us that Denisovans interbred with the earliest modern humans that passed

through their territories. More significantly, there is every reason to link the

Denisovans with the sudden acceleration in human behavior known to have occurred

in southern Siberia between 20,000 and 45,000 years ago. This included the making

of some of the first bird-bone flutes anywhere in the world, along with the creation

of settled habitation sites, the employment of advanced hunting techniques, the

formalizing of tool kits, including the use of microblade technology, and the

first sustained appearance of a specialized form of stone-tool production known

as pressure flaking.

In

addition to this, there is compelling evidence that the earliest human societies

to occupy the Altai-Sayan region possessed an extraordinary knowledge of long-term

eclipse cycles. Evidence suggests they used a knowledge of these cycles to develop

complex, numerically based calendrical systems that would go on to permeate religious

cosmologies in many parts of the ancient world. All the indications are that this

grand calendrical system, as we shall call it, had its inception in southern Siberia

and might well have been inherited from the lost world of the Denisovans. There

are also tantalizing clues that the principal creative influence seen as responsible

for long-term time cycles and the inaudible sounds once thought to be emitted

by the sun, moon, and stars was identified with a cosmic bird symbolized in the

night sky by the stars of Cygnus, the celestial swan. Through this association

the constellation went on to become guardian of the entrance to the sky world,

through which human souls had to pass either to achieve incarnation or enter the

afterlife.

In time many of the technological, cultural, and cosmological achievements that appear first in southern Siberia circa 20,000–45,000 years ago, reach the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of southeast Anatolia and begin to flourish at key cult centers such as Göbekli Tepe. From here they are carried southward through the Levant to northern Egypt. On the banks of the Nile River, as early as 8500–8000 BCE, they find a new home at a site named Helwan, which is today a thriving industrial city immediately south of Cairo. Yet it was here, almost certainly, that the predynastic world of ancient Egypt would begin in earnest, and it would be just across the river, on the plateau at Giza, that the fruits of the Denisovan legacy would finally find manifestation in the greatest and most enigmatic architectural accomplishment of the ancient world—the Great Pyramid, built for the pharaoh Khufu circa 2550 BCE. As we shall see, its underlying geometry, which underpins the entire pyramid field at Giza, displays a profound knowledge of long-term time cycles, numeric systems, and sound acoustics, as well as a polarcentric cosmology featuring the stars of Cygnus. All of this might well have had its origins in southern Siberia as much as 45,000 years ago. Piecing this story together will require some patience. Yet those who persevere will discover not only tantalizing evidence of a lost civilization, but also the true founders of our own.

The cover to The Cygnus Key by Andrew Collins. Cover artwork by Russell M. Hossain.

About the Book ...

The Cygnus Key traces the origins of civilization to the Denisovans of Siberia circa 45,000 years ago, and shows that they displayed incredibly advanced human behaviour as much as 60,000-70,000 years ago. I also spend some time on why their mindset was so different to ours, and how this also led to the emergence of shamanism, as well as the earliest known forms of animism in Siberia. These, we find, became centred around the symbol of the swan, swan ancestry and the transmigration of the soul to a celestial realm of the dead in the form of a bird. This is evidenced in the swan cult of Mal'ta, near Lake Baikal, dating back 24,000 years.

The book additionally provides compelling evidence that many of our own human achievements in the Upper Palaeolithic age can be traced back to the Denisovans, including advanced stone tool technologies and the recurrence of the cosmic numbers that appear everywhere around the world from Mesopotamia to India, China, Cambodia and Java (something that my colleague Graham Hancock has been interested in for years).

I show the presence of these numbers on a complex calendrical plaque found at Mal'ta, which is 24,000 years old. They are present also in a very ancient Altaic calendar. I demonstrate how these cosmic numbers, which appear to centre around two base numbers, 216 and 432, seem to derive from an extremely advanced understanding of the relationship between the sun's precessional cycle and long-term eclipse cycles used to measure time. This, almost certainly, was the product of the Denisovan mindset, which was savant-like in every respect (a theory backed up by the Denisovan genome).

Music and the use of sound acoustics also probably began with the Denisovans and their earliest hybrids, as did music's associations with cyclic time, polarcentric cosmologies, the swan as a symbol of celestial music, and the so-called Music of the Spheres.

I show that several of these ideas eventually turn up at Gobekli Tepe circa 9600 BCE, having arrived via the Ural Mountains of Russia. Here at Gobekli Tepe the oldest enclosures were built to reflect a rigid 3-4 ratio known to be associated with the enhancement of sound acoustics.

From Gobekli Tepe these ideas would appear to have been transmitted outwards in all directions. I follow two directions - into Western Asia Minor and Greece, and also into Egypt circa 8500-8000 BCE. The stepping stone into Egypt and the Nile Valley would appear to have been Helwan, which is, in my opinion, not only the original An or Annu (Heliopolis), but also the primeval place of first creation mentioned in the Edfu building texts (I have three chapters on these).

One major key showing the transition between Gobekli Tepe and Helwan is the Helwan Point, a matter that the late Professor Klaus Schmidt had much to say about within an important, albeit obscure, article published in 1996. Several chapters feature Helwan, the importance of which has been much overlooked until this time.

Lastly, I show that all of these ideas came back together and climaxed with the construction of the Great Pyramid and its neighbours on the Giza Plateau during the Fourth Dynasty. Their grand design, along with the Pyramid Texts that adorned the sarcophagus chambers and corridors of later pyramids, reflect cosmological ideas that most likely originated in Siberia during the Upper Palaeolithic age.

In addition to this, I review the very powerful evidence that at least some Denisovans were of great stature, like the largest wrestlers of modern times. I show that myths and folklore of giants in both the Altai Mountains of Siberia, and also in neighbouring Khakassia, seem to preserve a specific memory of the Denisovans and their achievements, including their invention of musical instruments and their building of the first dams, irrigation channels, and even built constructions.

I

identity a site that I strongly believe to have been one of the key nerve centres

of the Denisovans and their hybrid descendants in southern Siberia. It is an elevated

natural amphitheatre of unimaginable magnificence in the Western Sayan Mountains.

I argue that it is one of the earliest lunar-stellar observatories anywhere in

the world.

The

Cygnus Key is published by Bear & Co (May 2018), and is available to order

now from

Amazon

and

from

Barnes

and Noble