Andrew Collins at Dun Aenghus

Andrew

Collins at Dun Aenghus

A NEW IRISH FOLK TALE

Ireland’s

Most Beautiful Goddess and the

Quest to Find the Mythic Origins of the Aran

Islands

By Andrew Collins

Our story begins a few years back. A day-dream induced vision showed a clear scene of the past—a wooden-framed boat covered in animal skins, bringing a small group of individuals to a rocky island somewhere off the west coast of Ireland. The time period was prehistoric, perhaps the Neolithic age. As the group clambered up rocks I felt they had come here because the place was special in some way, almost as if a dream or vision, like my very own, had inspired this quest of exploration.

I had the sense that the island in question had been an important place of settlement, initially during Neolithic times, and much later as a place of pilgrimage during early Christian times. Perhaps it was Skellig Michael, I reasoned, an important holy island I knew existed in the Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland. On consulting a map, however, the geographical location of Skellig Michael was certainly not where I had seen my island. This was much further north, in a major bay.

That bay, I quickly realised, was Galway Bay, located on Ireland’s western Atlantic coast. Three islands guard its entrance. They are the Aran Islands. Somehow they did feel right as to where I had been in my vision. So I read up on their history and found they possessed a variety of prehistoric sites, including three wedge-shaped dolmens dating to the early Bronze Age, circa 2500 BC. Moreover, in early Christian times the largest of the islands, Inis Mór (Inishmore), had become a major holy centre and place of pilgrimage. Indeed, its rise in Christian sanctity closely paralleled that of Iona in Scotland, with various Irish saints establishing important monasteries and chapels here by the sixth century AD.

Dun Aenghus and the Firbolg

I quickly became convinced that Inis Mór was indeed the site of my dream vision. Yet it was seeing one particular, extremely impressive monument on the island, that really took my attention. This was Dun Aenghus, a massive ring fort composed of four concentric rings of stone. These radiated out from a semi-circular enclosure located on the top of a 100-metre cliff face. At its centre was a raised square platform rising up from the living rock. Something told me that this massive stone fortress, over 3000 years old and located on the island’s southwest coast, was important in some way. But who exactly was Aenghus, the legendary figure behind the name Dun Aenghus?

Aenghus, I discovered, was thought to have been a celebrated leader of the Firbolg (or Fir Bholg), one of the mythical peoples of Ireland. They were descended of the Nemedians, the people of Nemed, who had been forced to flee Ireland following the arrival of an incoming people known as the Partholón. One group of Nemedians departed for Greece, while another migrated to the Arctic north.

Those Nemedians that reached Greece were enslaved by its inhabitants. Yet after many years of captivity their descendents, now known as the Firbolg, meaning “men of the bag,” were finally able to free themselves from the bonds of their Greek masters. They made their way back to Ireland via Iberia (Spain), and on their return they divided Ireland into five provinces and established a high kingship with nine kings that ruled for a total of 37 years. Thereafter came the Tuatha de Danann, descendents of those Nemedians who had fled to the Arctic north. Despite their ancestral commonality, the Firbolg and Tuatha de Danann engaged each other in battle, the latter defeating the former.

Some accounts say that the remaining Firbolg were vanquished to the most remote reaches of Ireland. Others say that after the fighting was done the Tuatha de Danann allotted the Firbolg one quarter of Ireland. Aenghus, or Oenghus, the son of Umor, was said to have been king of the Firbolg in the east, with the Fort of Oenghus (Dun Aenghus) “in Ara,” usually interpreted as meaning the Aran Islands, being named after him.

Despite the obvious defensive nature of Dun Aenghus I felt strongly that its construction masked a much greater function, one more liminal in nature. I was thus intrigued to discover that, according to local tradition, once every seven years the lost land of Hy-Brazil was visible from the Aran Islands. Hy-Brazil was said to exist in the direction of the setting sun, and when in sight would appear like a shining island, quite otherworldly in nature. It was my suspicion that the Aran Islands somehow preserved the last vestiges of an original population that still retained some knowledge of Dun Aenghus’s greater importance. Yet only by going there and experiencing Dun Aenghus first hand would I be able to learn more about the place.

The Quest Begins

Dun Aenghus and its mysteries remained strong in my mind until finally I was given the chance to visit the Aran Islands, courtesy of Ancient Origins co-founder Ioannis Syrigos. He offered to take me there during a visit to Ireland in December 2019. So on Wednesday, 19th December we drove from Dublin westwards to Galway Bay. At the port of Doolin we caught a ferry out to the island of Inis Mór. The journey was extremely rough. I actually felt sea-sick for the first time in my life! Yet after what seemed like a lifetime we finally made landfall at Kilronan, the island’s large village, and in the pitch-black darkness walked the 400 metres to our guesthouse. There was definitely an air of otherworldlyness about the place, almost as if the island was somehow familiar, even though I had never been here before in my life. Maybe I had come here in my dreams, or perhaps in some past life. Who could tell for sure.

After a meal in the imaginatively named The Bar, labeled as the oldest bar of its sort on the Atlantic, we retired to our rooms to get some sleep. Since visitors to the island are not permitted to use cars, in the morning we would have go out early to hire power assisted bicycles to travel the 7.5 kilometres out to Dun Aenghus. For me this was going to be somewhat of a challenge as I had not ridden a bike since I was a kid.

Andrew

Collins on a power-assisted bicycle.

The Dream of Angelina

That night I had a powerful and somewhat unexpected dream that would alter the entire course of our visit to the island. In it I had met a most beautiful woman with long flowing hair. Her name was Angelina, and, no, she had nothing to do with the famous film star of the same name! We seemed to be passionately in love, and spent a long night together that went on forever. The location of this encounter was the town of Kilronon itself, although I was not in the same guesthouse room. Time passed and in the dream I remember thinking that I would be late for breakfast with Ioannis, scheduled for 8.30am. Eventually, I recall leaving Angelina behind and going out for a walk with some friends. We walked through the town and on returning to the guesthouse I was approached by a group of men in modern-day clothes who were waiting for my return. They said that Angelina belonged to their boss and that he had now taken her back, seemingly against her wishes. More important, this boss had made it known that anyone who tried to take her away from him would get a serious beating, and that, of course, meant me!

As these men moved towards me, their fists clenched, I forced myself to wake up. Thinking the dream was over, I fell back to sleep and again encountered the same group of men, who seemed intent on giving me my just deserves. The last thing I recall was walking with friends along the western edge of a long lake or waterway. It appeared to curve around like a river might do. Somehow, the men were still in pursuit, coming across the water towards our position. Trying to get away from them, I recall climbing some hills to the southwest of the lake. I then launched myself into the air, flying across the lake, landing eventually in the water. I then began swimming back towards where I had started my journey, hoping that this would be enough to foil my pursuers.

So strong was this dream that on getting up that morning I felt compelled to write down everything I could remember about its contents. I sensed that the whole thing had some kind of symbolic meaning, well beyond any wishes, desires, anxieties and fears of the sort that might influence the contents of a “normal” dream.

Who then was the beautiful Angelina? Was she real, fantasy, or a metaphor for something else? Her name included the Latin word “angel,” meaning a “messenger of God,” so perhaps she was some kind of genius loci or spirit of the island. Then there was the group of men whose boss thought Angelina belonged to him. Who were they? Was the whole thing symbolic of a local pagan goddess cult being usurped by a later male dominated society? It was worth some consideration.

The Visit to Dun Aenghus

After some standing around in the cold next to the harbour, Ioannis and I were eventually able to hire the required power-assisted bicycles we needed for our journey across the length of the island. Wintery showers, including spiteful hail, rained down intermittently, soaking our clothes, and making the ride out to Dun Aenghus more than a little unpleasant. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, Ioannis stopped to point out our destination. On the top of a bleak hill ahead lay an array of stone ruins signifying the presence of Dun Aenghus. I was finally going to be able to experience the site for myself. What would we find? What would happen when we got there? Would I gain any answers as to why I had been led here in the first place?

Having reaching the base of the hill below Dun Aenghus, we took shelter from the rain in the empty visitors centre. We then climbed the rocky path towards the ring fort, which loomed ever closer with every step. Finally, Ioannis and I entered through a tall gateway in the outer perimeter wall, beyond which we saw an enormous circular wall, supported on the outside by enormous stone buttresses. Very clearly the whole thing had been reconstructed in fairly recent times, but the ambience exuded by the site was undeniable.

The

approach to Dun Aenghus from the direction of Kilronan.

The rain kept off long enough for us to enter the fort’s inner enclosure, with its raised square platform extending out of the living rock. If not an altar, it must have served some ceremonial or religious function. It could even have been the dais for a royal seat or throne. From here we were able to gaze out across the Atlantic, with the low midwinter sun almost directly due south. Somewhere out there, a little to the west of the sun, was the mythical realm of Hy-Brazil. I did look, hoping this lost land might come into view, but it didn’t. Obviously, we had arrived at the wrong time in its seven-year cycle. So we took some photos, before deciding to retire into a small tunnel-like recess. Here we could shelter from the incessant wind and annoying rain, which had now begun to fall again.

The Meditation

I felt this was now an ideal opportunity for us to conduct a brief meditation to try and attune to the site’s inherent energies. I suggested we see light radiating out in every direction, after which I acknowledged the site’s genius loci, asking him/her to both guide and guard us on our quest. With this done, we cleared our minds of all thoughts to see if we could receive any extraneous images and impressions that might help us learn more about the site.

Dun

Aenghus exterior wall with stone buttresses.

The

raised stone platform in Dun Aenghus’s inner enclosure.

The first thing I saw was a cattle skull on a pole. It was a brief, but strong image, suggesting the presence here in the past of a cattle cult of some kind. I saw also a large antlered deer, a powerful symbol of the Goddess from Siberia all the way across to Western Europe. Was the sight of this deer symbolic of the island’s genius loci, or guiding spirit? My mind went back to the beautiful woman of my dream. Was she really some kind of female spirit, a goddess perhaps, associated with the island?

The only thing I could add was the sense that the connection between the deer and the island was not at Dun Aenghus, but away towards the west. This was the direction of Eoghanacht (pronounced On-nacht), a tiny village we were planning to visit after our departure from Dun Aenghus. Why exactly will require some explanation.

The Search for Antonin Artaud

In 1937 the French dramatist and poet Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) had arrived on Inis Mór wielding a walking stick he believed was the staff of St Patrick. His purpose was to return this assumed holy relic to the “sources of a very ancient tradition.” Earlier that week a friend had asked me to try and follow in his footsteps, and perhaps attempt to find out where he had stayed when on the island. On the ferry across from the mainland I had checked online and found that on arrival on Inis Mór Artaud had secured lodgings at the home of one Seán Ó Milleáin of Eoghanacht. Having told this story to some of the local traders at the base of Dun Aenghus (one of whom responded, “Was that the guy who came here shaking a big stick around?”) I was directed towards one of Ó Milleáin’s now elderly descendents. This was an 80-year-old woman who lived in Eoghanacht. Apparently, she was one of the last people alive who could sing in an ancient Irish folk style that more resembled wailing than actual singing.

Intent on speaking to her, Ioannis and I now cycled out to Eoghanacht, where among the scatter of houses either side of a single road we found the cottage owned by the woman in question. Sadly, however, she was not at home when I called. This was a terrible shame. Neighbours, however, confirmed that she was the niece of Seán Ó Milleáin, and so would almost certainly have known something about Artaud’s visit to the island, in particular his brief time lodging with her uncle.

Realising that time was ticking by and that we needed to return to Kilronan by four o’clock that afternoon to catch the ferry back to the mainland, we began our return journey, the weather now a little more favourable. Just up the road, however, I stopped to take a photo of a sign on the right-hand side of the road. It pointed up a track to somewhere called Dun Eoghanachta, another cliff top ring fort I presumed, linked in some way with the village of the same name. We didn’t have the time or inclination to see the fort for ourselves. Yet taking a picture of the sign seemed important for some reason, after which we resumed our journey back to Kilronan.

Stone

cottage at Eoghanacht, Inis Mór.

God or Goddess of Love?

On arrival in Kilronan the bicycles were dropped off, and since we were a little early for the ferry’s departure we went into The Bar for a quick drink. By now I had become convinced that the Angelina of my dream was indeed a female spirit associated with the island. So using my phone to look online I unexpectedly found something of direct interest to this story. Although the Aenghus behind the place-name Dun Aenghus is usually identified with the Firbolg leader of this name, some historians have identified him as Aenghus Óg, the Irish god of youth and poetic inspiration, who was also a member of the Tuatha de Danann. More important is the fact that this Aenghus was the Irish god of love. Indeed, it is said that his kisses took the form of four singing birds that flew constantly around his head. Since I had always assumed that the Aenghus associated with Dun Aenghus was the Firbolg leader this new discovery got me thinking.

Was it not strange that a deity presiding over love should be male? Surely this was the domain normally of a female divinity, like Aphrodite in Greece, Venus in Rome, or Hathor in Egypt. Yet here in Ireland the deity of love was a male! This seemed a little odd to me. I then found out something else. The feminization of the male name Aenghus was Angie, the shortened form of Angelina! Clearly, this had nothing to so with the root of the name Angie, which derives from the Latin word “angel.” However, the similarity between Angie and Angelina, the woman of my dream, was undeniable.

The Cult of Áine

I then looked into the root of the Irish name Aenghus. It derives from the Gaelic word aon, meaning “one,” which comes from an Indo-European root found in various allied languages as aine, aina, ein, and a´n, all of which mean “one,” “the first,” “only,” the “only one,” etc. It was then that I discovered something else that cannot be without meaning. Áine (pronounced something like ein-ya or, more commonly, arn-ya) is the name of an Irish goddess of love. She was the provincial goddess of Munster, which once covered much of southern Ireland, south and east of Galway Bay.

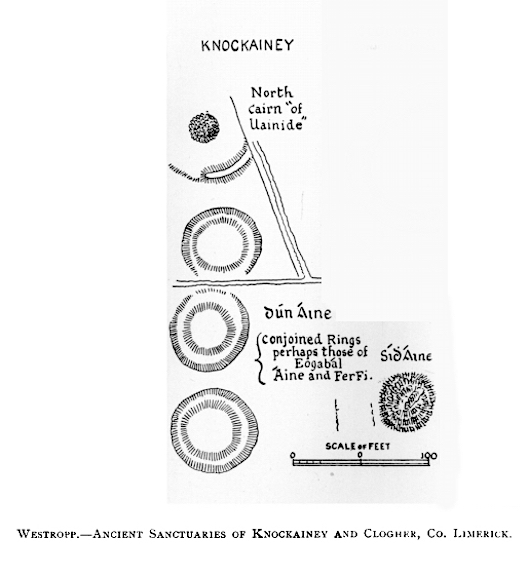

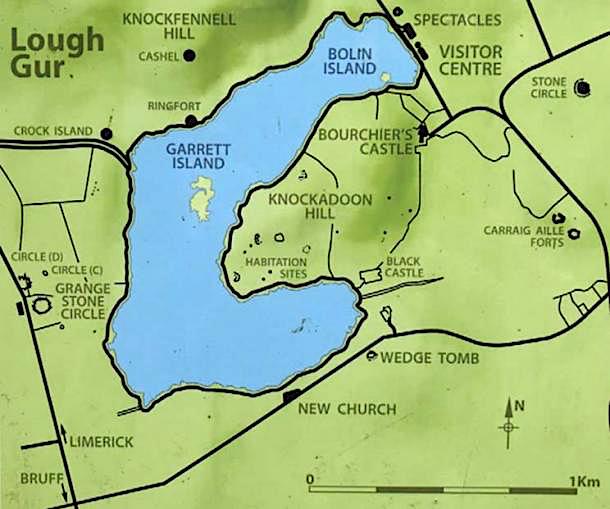

Áine was not only goddess of love and fertility, but also of the sun (and perhaps even the moon). The feast of midsummer’s eve was conducted in her honour. Her chief seat was Knockainey (Irish Cnoc Áine), a holy hill near her sacred lake of Lough Gur in Co. Limerick. A cairn on the hill’s summit known as Sidhe Áine was seen as the entrance to her otherworldly palace. Three ring barrows nearby are thought to be the burial sites of three great ancestors of the kings of Munster. One, Dun Áine, is said to be that of the goddess herself. Another is thought to house the remains of her father Eoghobal, a druid and member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, with the third being that of a musician named FerFi. Around Lough Gur itself is one of Ireland’s most densest concentrations of prehistoric sites. Among them is what is arguably the country’s most impressive stone circles, this being the Grange stone circle, called in Gaelic Lios na Gráinsí, the “Fort of the Grange.”

The

cairns and ring barrows on Knockainey Hill, Co. Limerick, Ireland (from Westropp,

1917).

Áine was known in Munster as Queen of the Fae (Fairies), as well as Áine Chlair (“Áine of the Light”), through which she was associated with the sidhe mounds of the Bronze Age peoples. It was through these sidhe that the Tuatha de Danann are said to have departed the physical world on the arrival of a mythical people known as the Milesians, who are often identified as the incoming Iron Age Celts.

The Rape of Áine

According to folk tradition Áine was viciously pursued and raped by Ailill (also spelt Oilill or Olioll), a legendary king of Munster. During the struggle the goddess bit off his ear, hence his epithet of Olum, meaning “the earless.” I would not be the first to point out that in this story is the attempted suppression of a goddess cult by an incoming male society. Indeed, there is an air about the defilement of Áine echoed in the manner that the woman named Angelina in my dream was being held against her will by the leader of a gang of men who wanted to beat me up for trying to take her away from him. Was it really possible that Angelina was in fact the goddess Áine, the Celtic goddess of love? It was certainly beginning to feel that way.

Even more interesting is the fact that according to an ancient Irish text known as the Silva Gadelica Ailill Olum’s encounter with Áine took place at her sacred sanctuary of Knockainey, which lies to the southeast of Lough Gur. He had been told to go there by his chief druid Fearcheas mac Comain after the king had found that every time he fell asleep the grass in the fields refused to grow. Since this threatened to destroy the kingdom’s livestock, which relied on the grass for its food, he accepted the word of the druid and on Samhain Eve (31st October) went on a pilgrimage to Knockainey. Here, he thought, a solution to his dilemma would be revealed, but instead Ailill fell into a drowsy half-sleep, after which he found himself sleep-walking. Thereafter he encountered a beautiful vision in the form of the goddess Áine. Overwhelmed by lust and desire he forgot his royal dignity and forced himself on the goddess at the place of her greatest sanctity. Yet by biting off his ear the goddess deprived him of his right to become high king of Ireland, since it was said that any candidate for this role had to be unblemished. Clearly, there is a connection here with the fact that Áine presided not just over the fecundity of the land, but also over kingship and sovereignty. Both would have been administered from her seat at Knockainey. In a separate tale, Áine uses magic to kill Ailill, while Ailill’s chief druid, Fearcheas, kills Eoghabal, Áine’s father. All of these stories probably have some kind of symbolic meaning, or are metaphors for the triumph of one particular human group’s beliefs over another.

Lough Gur

Although Áine’s name is commonly believed to derive from a Gaelic word meaning “bright,” its root comes from the more simplified form Án, which, as I had already realised, is Indo-European in origin and means, simply, “one,” “the only one,” or “the first.” In this role Áine was thus an expression the genius loci of Lough Gur’s ritual landscape, personified through the area’s rich concentration of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments.

In fact the more I read about Lough Gur, which has a very distinctive C-like or sickle-shaped appearance, the more I became convinced that it was this lake that I had seen at the end of my dream sequence. I recall trying to get away from my pursuers by climbing some hills to the southwest of the long waterway, and on looking at a map of Lough Gur I saw that it too has prominent hills just beyond its southern and western shorelines.

Map

of the Lough Gur area, Co. Limerick (picture courtesy of the Lough Gur Heritage

Centre).

Cattle Cult

The goddess’s totems include the Lair Derg, the “red mare,” the horse being a key symbol of kingship in the pagan beliefs and practices of the high kings of Ireland. Áine in her role as Queen of the Fae (or Shee) was said to arrive at Lough Gur in a coach and four, the vehicle’s horses apparently being headless. In other folk stories she became a comb-holding siren who would sit on her “chair” on the edge of Lough Gur enticing mortal men into her otherworldly domain. Indeed, it was said that she “often gave her love to men, and they called her the Leanan Sidhe, the Sweetheart of the Sidhe (Lady Gregory, 1904, Part I Book IV: Aine).”

One other important point, however, was the fact that she presided over cattle and cattle farming, even taking the form of a cow herself. Hundreds of offerings have been retrieved from Neolithic and Bronze Age sites around Lough Gur including an extremely large number of cattle skulls. The first image I saw during the meditation at Dun Aenghus was a cattle skull on a pole. Even then I had suspected that it was representative of some kind of cattle cult on the island. Just maybe this was an allusion to the cult of Áine, either in the kingdom of Munster, or perhaps on the Aran Islands. So was it possible to find evidence of Áine’s veneration on the islands?

The Eoghanacht of Áine

Incredibly, the answer is yes. For although Ailill Olum, the king of Munster was seen as unfit to rule Ireland as high king following his defilement of the goddess at her sanctuary of Lough Gur, his direct descendents, through his son Eoghan Mor, would themselves become kings of Munster. They are remembered as the Eoghanacht, a powerful royal dynasty that ruled from its seat at Cashel, Co. Tipperary, from the 6/7th century through to its demise in the 10th century AD. This said, ancient Irish annals and folk tradition make it clear the Eoghanacht must have thrived in Munster long before this time. The Eoghanacht’s tutelary goddess was Áine, from whom they claimed descent. Indeed, the branch of the Eoghanacht that claimed Kockainey as its seat, bore the name “Eoghanacht [of] Áine,” honouring their descent from the goddess.

Eoghanacht, of course, was the name also of the small village to the west of Dun Aenghus, where Ioannis and I had gone to track down any living descendents of Seán Ó Milleáin, who in 1937 had given lodging to the French dramatist and poet Antonin Artaud.

Eoghanacht the village probably takes its name from the nearby ring fort of Dun Eoghanachta (the slight difference in spelling deriving simply from local variations in word usage), which I determined does indeed take its name from the Eoghanacht royal dynasty of Munster (Ó Maoildhia, 1998, 76). They arrived on Inis Mór either in the late Iron Age or during the early centuries of the Christian era. It is interesting to note that one of Inis Mór’s most celebrated Christian saints, St Enda, was given special permission to establish a monastery here in the mid sixth century by the ruling king of Munster. This shows the influence of the kings of Munster over the Aran Islands by this time.

Unquestionably the Eoghanacht, as pagans, would have brought with them the worship of the goddess Áine. Their chief seat would have been Dun Eoghanachta with their settlement most likely located on lower ground, probably in the vicinity of the village of the same name. It is even possible that some of Eoghanacht’s inhabitants are descendents of the Eoghanacht of Munster. The interesting fact here is that had I not gone in search of Antonin Artaud on Inis Mór I might never have known of the existence of Eoghanacht and Dun Eoghanachta.

Back to my Dream, and Angelina

One final fact linking my dream of Angelina with the goddess Áine is the fact that in an article published in 1852 within a folklore magazine about the survival of the cult of the goddess at Lough Gur it states that one form of her name is Aighne (O’Kearney, 1852, 35), probably pronounced something like eign-ya or eign-ja. This is so phonetically similar to the name Angie that it convinced me finally that the woman of my dream had indeed been the goddess Áine.

The

sign pointing the way to Dun Eoghanachta.

Why exactly the goddess should have appeared to me in the manner she did presumably had something to do with me helping to keep her name alive by writing articles such as this. Doing so will ensure the continuance of her veneration not just on Inis Mór, but also at Knockainey, the “Hill of Aine,” where even to this day celebrations in her name take place every midsummer’s eve (June 23rd).

For in my opinion Áine, as the true root of her name suggests, was the “only one,” “the first” goddess, from whom all life was thought to spring. Very likely she existed in her most primal form among the Neolithic peoples of Munster. This was once seen as a primeval world in its own right, a place of origin of the Irish peoples. Áine’s veneration was then kept alive during the Bronze Age and eventually emerged in a more recognisable form with the rise of the Eoghanacht royal dynasty during the Iron Age. They were the descendents of Eoghan, whose own father, Ailill Olum, the king of Munster, had defiled the goddess at her most sacred shrine of Knockainey. The Eoghanacht would eventually take up residence on Inis Mór, somewhere around Dun Eoghanachta and the village of Eoghanacht, the reason why her influence on the island was strong enough to reach me in a dream.

As regards Dun Aenghus, and my quest to discover its inner mysteries, a local book I purchased in a craft shop at the base of the hill provided me with the answer. The ring fort’s inner sanctum, with its raised stone platform, has long been considered a liminal place, from which the souls of the deceased were once thought to depart westwards across the Atlantic Ocean to the otherworldly realm of Tír na nÓg, the Land of Youth (Ó Maoildhia, 1998, 71). I also found out that it was from here specifically that the mythical island of Hy-Brazil became visible as a shining vision once every seven years, making it clear that one of the primary reasons for the construction of Dun Aenghus was as a perceived point of access to these otherworldly locations. So, one day, I shall return to the Aran Islands to fulfill my own journey to Tír na nÓg, although hopefully not before a second encounter with the beautiful Áine, the Irish goddess of love.

Bibliography

Gregory, Lady. 1904. Gods and Fighting Men. London: John Murray (see http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/gafm/gafm15.htm).

O’Kearney, Nicholas. 1852. “Folklore No. 1,” Transactions of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society 2:1, 32-39.

Ó Maoildhia, Dara. 1998. Pocket Guide to Árainn: Inis Mór, Aran Islands. Árainn, Co. na Gaillimhe, Ireland: Aisling Árann.

Westropp, Thomas Johnson. 1917/1919. “The Ancient Sanctuaries of Knockainey and Clogher, County Limerick, and Their Goddesses.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 34, 47-67.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go out to Ioannis and Joanna Syrigos, Sophie Sleigh-Johnson, and Lorcan O'Toole.